As I stand in the Lausanne train station holding a sign saying “Marcel,” the volume of passengers from platform 8 dwindles from a steady flow to a trickle to a stop. He probably exited the other end of the platform. I stay put like you’re supposed to when you’re lost. He was the 20-something computer geek. I’d let him find me.

Sure enough, a few minutes later, he does. This amiable, t-shirt-clad student has come all the way from Zurich after his 8:00 class at ETH to show me how to play a protein folding game called FoldIt. The IT dude in my novel is a player, so I have to learn it, too.

In EPFL’s Rolex Learning Center a half hour later, we quickly download the game onto my Macbook, since his HP is bugging, and he logs into his account. A list of protein puzzles appears, with names like quick fix the loop puzzle, New Player Puzzle: Pollen Allergen Protein, Quick Flu Design Puzzle 3, Symmetric Foldon Puzzle 1. Underneath each puzzle is a brief description. Here’s one:

Foldon is a small, 27 residue domain from the C-terminus of a phage virus protein called fibritin. Your job is to fold 3 chains into a larger trimeric domain that includes foldon. You’ll be allowed to move foldon around as well, but you can only mutate the residues in the polyalanine extension. And remember, three-fold symmetry will be enforced! If you are new to Foldit, make sure you have completed Intro Puzzle 5-2, & 7-1 through 7-4. More details in the blog.

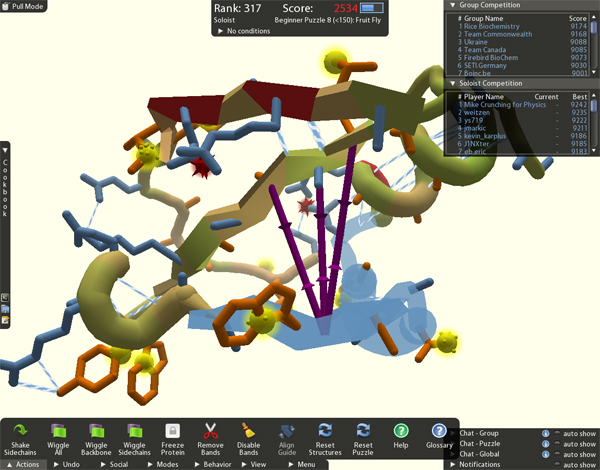

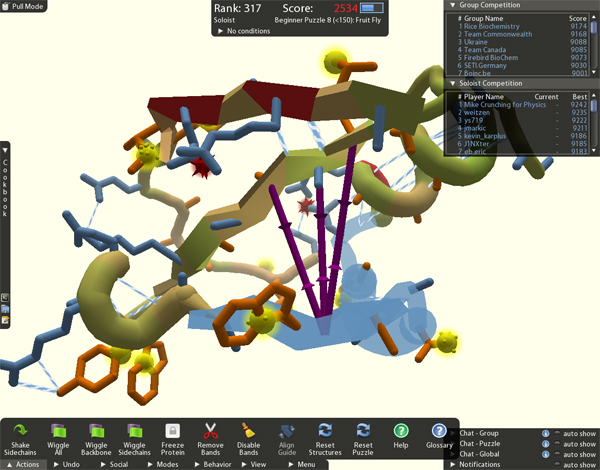

Holy crap, what am I getting into? I think. But Marcel dives right in and puts the flu design protein up on the screen. The backbone, he explains as he twists the protein around, is made of amino acids, arranged in macaroni-like helixes, flat sheets and sausagey loops. Poking out from it are key-like side chains, the blue ones hydrophilic, or water-loving, and orange ones hydrophobic.

He shows me how to zoom and twist the protein around, how to put purple rubber band-like things onto various arms of it and pull it together or stretch it apart, how to change a loop to a helix to a sheet, and how to freeze one bit and tweak another. Hydrogen bonds, which look like blue-and-white barbershop poles, like to form between sheets and along helixes, he explains, showing me how to line them up.

Angry red bombs appear when things get squashed too tightly together – clashes. Big, pulsing red blobs appear when there’s too much empty space – voids. You want to avoid those. We fiddle with the side chains, rotating the orange ones in and the blue ones out. He even shows me how to “mutate” them.

The whole time, he’s keeping one eye on the score that’s evolving in the upper part of the screen. He makes a move that results in a huge loss of points; our score plunges into the negative numbers, turns red, and lots of red bombs appear. “Quick! Put it back!” I panic.

“Hang on,” he laughs. He’s totally relaxed. “Now we’re going to wiggle and shake.” He clicks a button and the whole structure starts bouncing, complete with a ticking soundtrack in the background. I watch as the points move rapidly upwards out of the red, then gradually slow down, while still increasing. After a while, Marcel clicks the wiggle off. Our total is higher than it was before! Then he clicks another button and all the side chains start rotating. Once again, the score ticks upwards. We sit back, satisfied.

The points represent energy, he explains. The native structure of the protein is going to be its lowest energy state. The higher the number of points, the lower the energy state. But like a ball on a golf course, you can get stuck in a local minimum and miss the hole you’re shooting for. “It’s like this building,” he says, looking at the undulating floor of the Learning Center. “A ball will roll down into a hole. But that doesn’t mean it’s the lowest hole around. It’s just the one it was nearest.” Sometimes you have to pull back quite a ways and shake things up to get the ball to roll into a deeper hole – a lower energy state.

When a protein is manufactured in the cell, it zips into this native shape in no time flat. The shape is critical to the protein’s function. Sometimes, if the environment isn’t right or there’s a problem with an accompanying protein, called a chaperone, the folding doesn’t go right. Misfolded proteins are implicated in a variety of diseases like mad cow, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and cystic fibrosis.

Scientists would dearly like to be able to predict the structure of proteins, because then they could design drugs that could fix the misfolded ones, or disable the harmful ones in viruses or bacteria. With this kind of knowledge, perhaps some day new proteins could be engineered for gene therapy or other medical miracles.

Algorithms to predict structure chug along on huge servers or in distributed computing networks, like rosetta@home, which uses spare CPU on home computers to run its calculations, but they take forever because they have to brute force every conceivable possible convolution. There’s no guarantee the algorithm will find the lowest energy state, either, even after all that calculating. It’s a really complicated problem. FoldIt taps into something these algorithms cannot – human intuition and pattern-finding capabilities.

Marcel shows me the different puzzles available – they range in difficulty from easy structures put up for newbies like me to complex proteins involved in actual scientific research. There are only a few on at a time, each one with an open window of about a week, in which players work either on their own or in teams to get the highest possible points before it “closes.” You can “evolve” a protein, which means you work on a solution, and then share it with other people, who then add their bit to it, and so on. The protein’s structure then progresses as a joint effort. You have two rankings – “solo” and “team,” based on your results in each category. Marcel is a member of the Androids team.

He estimates that there are about 300 really active players, spread all over the world. The master solo player is a guy from Slovenia called Wudoo. A woman in Texas with a couple of kids, jpilkington, is the “evolver queen,” he tells me in reverent tones. While we’re playing, she comes online and starts chatting with other players. I tell her my brain is exploding. “LOL,” she replies.

Rav3n_pl, a programmer who lives in Poland, is a master at writing “scripts” –recipes that apply long strings of commands to the protein, which can be run in the background for hours while you’re off doing something else. Marcel started the flu design puzzle that morning. He first did a few manual tweaks, and then ran one of Rav3n_pl’s genetic algorithm scripts while he took a shower and ate breakfast. “The manual stuff can only take you so far,” he explains. After that, you eke out points at a time by running scripts. (These recipes, BTW, are the subject of a recent article in PNAS.)

As we continue to work the protein, I see what he means. The score appears to be stuck. “The deeper you are in an energy hole, the harder it is to move something,” he says. He opens the “cookbook” he has set up on the left hand side of the window and starts a script. We watch the protein jiggle and shake, the points fluctuating wildly as it starts, stops, reverts and starts another iteration.

Finding your way out of the hole is an art. There are a few people who are consistently among the top scorers, he tells me. “It’s not just luck. There’s something – either they have an intuitive feel for how the programming works, or they see patterns, or maybe they just have good computers and can run tons of scripts.”

Marcel has been away for a couple of weeks on military duty. Even so, his overall rank is 61. Wow, I say, you must play all the time!

“No, not more than an hour or two a day, max,” he assures me. “And a lot of that is just scripts running.” He admits, though, that when a deadline is approaching, he might put more time in with his team.

Well, sure, but you must also know a ton about molecular biology, in order to be able to rack up a ranking that high?

“Nope,” he says. “I just like getting the points. Sometimes you make a move, and you get a few points, and the protein just looks right, and it’s an amazing feeling.”

He also likes the social aspect of the game. “I’d never just play it offline,” he says. “I like chatting with my teammates. What should be the next step? What’s going on in their lives?” True. He is a chatty guy. He’s spending the entire afternoon with me, an uber-noob novelist, after all.

I figure he got into the game because he’s a chemistry student. “Not really,” he tells me. “At first, I looked into the seti@home thing, but then, really, who cares about aliens? I found rosetta@home, and that was cool, proteins are important, and it was there that I found out about FoldIt.”

Finally, we open the most recent puzzle on the site, something called a CASP roll, a “freestyle” protein with 197 amino acids that has to be folded from scratch. Sometime in February, the best FoldIt solutions will be compared with solutions cranked out by algorithms running on servers and with experimental data from x-ray crystallography and nuclear magnetic resonance imaging.

“Just look at that!” Marcel says as we contemplate the unfolded backbone stretching off into the screen. “197 amino acids! It’s huge!”

The CASPs are cutting edge science. A previous CASP puzzle solved by FoldIt gamers was published in Nature in September. Researchers had been struggling with an enzyme in a monkey version of the HIV virus. Despite the existence of several crystal forms of the protein, they were unable to solve its structure computationally, even though they’d been working on it for a decade. But if they could figure out its structure, they could engineer a way to disable it, thus hobbling the virus. They posed it as a FoldIt challenge, and within three weeks, two teams of FoldIt players (the Contenders and the Void Crushers) came up with multiple possibilities for its structure, enabling the scientists to further refine the game, which in turn led to the discovery of several molecular targets on the structure that can now be used to develop retroviral drugs.

As I drove Marcel back to the train station later that afternoon, I felt a little guilty. He’d spent his whole afternoon playing FoldIt with me, and his score hadn’t moved a whole lot. But then I remembered he had a two-hour train ride to Zurich, and a USB internet key.